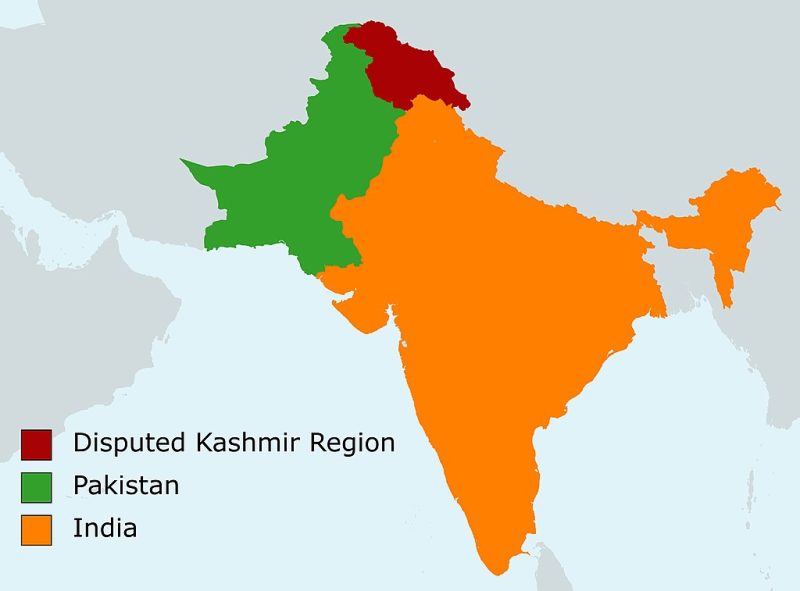

On June 24th, Pakistan’s army claimed that Indian forces killed two civilians after opening fire on a group of shepherds in the disputed Kashmir region’s Sattwal Sector, at the Line of Control, the de facto border between the two countries. According to Reuters, this is the first such conflict since the two countries’ joint ceasefire agreement in 2021.

Kashmir has been the cause of two wars between the nuclear powers and has continued to be a major source of tension in recent years. The army’s statement warned that the deaths give Pakistan a right to strike back.

The conflict over the Muslim-majority Himalayan territory began in 1947 when India, West Pakistan, and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) were created in the Partition of the Indian subcontinent following independence from British rule. Though neither India nor Pakistan fully controls the Kashmir region, both nations claim Kashmir in its entirety. A provisional militarized control line officially established by the 1972 Simla Agreement divides the region. Spanning 477 miles, the Line of Control is marked by landmines, tunnel detection gadgets, and military outposts. The Line cuts off villages and communities along each side, preventing free movement and separating families already devastated by the continuous border skirmishes and ceasefire violations between India and Pakistan.

In 1989, Kashmiris became increasingly dissatisfied with the Indian government following controversy over rigged elections and political alliances with the Indian National Congress, as well as a lack of channels for political participation. Throughout the next decades, separatist sentiments and militant groups began to grow in Kashmir – as well as Indian military and counterinsurgency involvement, ultimately costing tens of thousands of lives.

In 1999, meanwhile, Pakistan’s generals secretly ordered a tactical operation to occupy heights in Kargil. India’s response to these incursions sparked the Kargil War, which resulted in hundreds of casualties and displaced thousands of civilians on both sides of the Line of Control. The absence of a proper government rehabilitation program for those who fled their villages in Pakistan left tens of thousands displaced and unable to return home. In addition to the difficulty of moving across the Line of Control, Kashmiris have experienced violence, damage to their homes and livelihoods, and economic hardship. The region is dependent on agriculture, and many farmers who were forced to flee bore the brunt of livestock and crop loss.

Despite the establishment of a ceasefire agreement in 2003, India and Pakistan have continued to exchange fire across the border. In February 2019, an attack by Pakistani militant group Jaish-e-Mohammad on a convoy of Indian paramilitaries in Indian-administered Kashmir killed at least 40 soldiers. When India conducted air strikes inside Pakistani territory in response, Pakistan retaliated with air strikes. In August 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, leader of India’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, sent hundreds of thousands of Indian troops into Kashmir after signing a decree stripping Kashmir of its special status and constitution without consulting Kashmiri elected representatives. In order to prevent unrest and protests, the government cut landline, mobile, and internet communications and imposed a curfew. Pakistan’s then-Prime Minister Imran Khan called the unilateral revocation an illegal annexation, and called for bilateral negotiation and international intervention.

Foreign governments and human rights organizations such as Amnesty International have criticized India for its treatment of Kashmiris in recent years. The Indian government continues to suspend internet services, arbitrarily arrest journalists and dissenting political activists, and grant its security forces dangerous levels of impunity to silence opposition thanks to counterinsurgency and counter-“terrorism” laws. Meanwhile, minority Hindus in the region continue to face violence from separatist militants gaining support due to increasing dissatisfaction. This feedback loop of rampant state repression, violence, and militancy will only continue if opposing voices and democratic channels of voicing dissent are brutally shut down.

Attempting to bring peace to the region in light of the record levels of ceasefire violations, the directors general of military operations of India and Pakistan declared a commitment to a ceasefire along the Line of Control in a rare joint statement in February 2021. An assessment by Carnegie India the next year showed reduced ceasefire violations and flare-ups on both sides of the Line of Control, and an increase in development funding, private investment, and tourism. India has advertised this image of renewed stability and prosperity in recent years; “The region was a terrorist hot spot. Now it has become a tourist hot spot,” said Amit Shah, India’s home minister. However, the newfound “stability” in Indian-administered Kashmir has come with extreme militarization and continued human rights violations.

Despite the joint ceasefire agreement, India and Pakistan have been unable to find long-term, bilateral solutions to the Kashmir dispute. India is largely unwilling to negotiate with Pakistan or Kashmiri separatist parties, claiming that issues pertaining to Jammu and Kashmir are internal, and has worked to further militarize Kashmir. For its part, Pakistan’s alleged contributions to tensions on the border and support for militant separatist groups have served as a source of tension between Pakistan and India. However, Pakistan has urged India to enter bilateral negotiations due to its violations of previous agreements, and has called on the international community to address the human rights abuses India has committed in Kashmir. “The onus is on India to create a conducive environment for talks,” Pakistani foreign minister Bilawal Bhutto Zardari said during his address at the Shanghai Co-operation Organization (S.C.O.) summit India hosted in May 2023. The diplomatic strain at the S.C.O. was evident as Bhutto Zardari and Indian foreign minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar exchanged indirect public exchanges regarding the revocation of Kashmir’s special status, with Jaishankar, who is a member of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party, going so far as to call Bhutto Zardari the “spokesperson of a terrorism industry.”

Mosharraf Zaidi of Pakistan-based public policy think-tank Tabadlab drew special attention to the Islamophobic weaponization of the word “terrorism” and India’s treatment of Pakistan in public discourse in an interview with Al Jazeera. “India’s hatred for Pakistan is existential and cuts across all political parties,” Zaidi said, “but is especially stark and profound when it comes to the Bharatiya Janata Party.”

Still, Kashmir itself got little recognition at the talks beyond serving as fodder for each country’s criticism of the other. “These are the voices you never get to hear, yet these are the people who are affected most by the political tensions,” Pawan Bali, a conflict resolution expert with experience in India-Pakistan issues, told the Global Press Journal in 2019.

“Both foreign ministers were more worried about the internal politics in their own countries than making any progress on issues concerning their foreign policies,” Sushant Singh, a senior fellow at India’s Centre for Policy Research, told Al Jazeera.

In a report for the United States Institute of Peace regarding a possible peaceful resolution in Kashmir, New Delhi-based professor Happymon Jacob pointed to the backchannel negotiations that took place between 2004 and 2007 with interlocutors selected by India’s prime minister and Pakistan’s president, as well as, importantly, both mainstream and separatist Kashmiri politicians. During these meetings, former Pakistani President Musharraf reportedly proposed a four-point model for a resolution, though the unstable political climate in Pakistan meant that the deal ultimately went unsigned. This four-point solution required both Pakistan and India to demilitarize in the region, create a level of self-governance for the entire former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, remove “irrelevant” borders to enable trade and free movement throughout the region, and establish joint management between India, Pakistan, and the two Kashmirs. However, to reconsider this type of solution, the B.J.P. must be willing to stop treating Kashmir as a “domestic” issue and put a stop to the decades of democratic repression and human rights violations it has effected in its militarization of the region. Currently, this looks unlikely. Until India prioritizes democracy, human rights, and Kashmiri involvement in bilateral negotiations with Pakistan, it will be unable to stop the violence.

It is essential that the Kashmiri voices which have been brutally repressed in Indian-administered Kashmir are present at any future negotiations. As history and recent news have shown, despite Pakistani and Indian commitments to peace in the region, existing agreements regarding Kashmir and the Line of Control have been unable to address the physical, psychological, social, and economic dangers which continue to impact Kashmiris on both sides of the line. Kashmir has served as a battleground for the interests of two countries in conflict, with its people becoming collateral damage and being left unrepresented and voiceless. The most important key to a long-term solution to the conflict in Kashmir is listening to the voices of Kashmiris living on both sides of the Line of Control.

- Women Seek Compensation For 1960-70s Danish Involuntary Birth Control Campaign - February 13, 2024

- Venezuela holds military drills following the arrival of British warship in Guyana - February 11, 2024

- Iraqi P.M.’s Intent To Cede Military Command To Kurds Sparks Protests, Killing Four - September 15, 2023