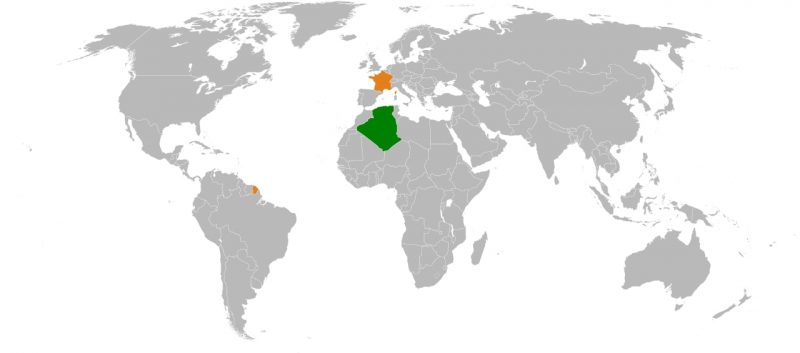

On August 25th, Emmanuel Macron arrived in Algeria, five years after his last visit to the North African ex-colony. The goal of this three-day visit, which saw the French president accompanied by a delegation of over 90 politicians, businessmen, and intellectuals – including many bi-nationals – was to repair Franco-Algerian relations and to therefore boost future economic relations.

Algerian president Abdelmadjin Tebboune called the visit “excellent, necessary and useful.” The two countries signed a declaration for a renewed partnership, as well as four agreements of bilateral co-operation on health, scientific research, technological development, and education.

Franco-Algerian relations have been strained in the recent past because of some comments President Macron made last year, accusing Algeria of instrumentalizing past grievances and rewriting history to encourage hatred towards France. In response to such strong allegations, which were contradictory to a previous statement from the Elysees, Algeria withdrew its ambassador.

Algeria was part of the French colonial empire for 132 years, finally achieving independence with the Evian Accords of 1962. The decolonization process was anything but peaceful: the brutal eight-year war killed half a million people – according to French historians – and left a stain on French politics and society. Macron is the first French president born after the war, but also the only one who, during his mandate, has made efforts to acknowledge the tortures and the killings committed by the French.

Despite going so far as to call these actions a “crime against humanity,” Macron has still failed to issue a formal apology.

More than a simple colony, Algeria was a province of France. Even now, 60 years after independence, its deep connection with French culture and society is palpable. At the same time, Algerian influence is still present in French domestic politics because of the millions of French citizens and residents linked with Algeria – immigrants with their children, bi-nationals; descendants of the “Pieds-Noir,” the French who were born in Algeria during France’s occupation and who largely traveled to France after independence. Not only that, but Algeria is an essential strategic ally in France’s mission against Islamic extremism: the country shares borders with Mali, Libya, and Niger.

The war in Ukraine has also elevated Algeria’s importance to Europe in terms of energy supplies, now that the West is looking to diversify its suppliers. Economic factors were not the focus on Macron’s visit and no major agreement has been signed on that front, but creating a strong partnership would allow France to negotiate deals in the near future.

One of the initiatives the parties have agreed to is the creation of a commission of historians to inquire into the colonial past in what Macron called a “quest for the truth.” France has agreed to open its archives to compare them against the Algerian ones, looking to solve all incongruences in order to embrace a more objective view of the countries’ common history. For this purpose, the commission will be treating the question of memory from a purely historical, not political, angle: “depoliticized,” is how President Tebboune defined it.

Macron’s visit may have succeeded in normalizing bilateral relations between France and Algeria, but while the visit seemed to have focused mainly on making amends, France still seems worried to lose its sphere of influence in North Africa. The Elysees have clearly realized that Algeria has been shifting its attention away, sealing economical deals with some countries and strengthening political ties with others – China and Russia in particular. Macron’s visit therefore appears to be less about redemption and more about a colonial mindset which, despite assuming a different modality, still hasn’t left French politics.

- Further Steps Towards Improving Egyptian-Qatari Relations: El-Sisi In Doha - September 29, 2022

- Voters Reject New Constitutional Draft in Chile - September 22, 2022

- Coming To Terms With The Colonial Past: Macron’s Visit In Algeria - September 18, 2022